GROSSADMIRAL RAEDER TESTIMONY AT THE NUREMBERG TRIALS

(Excerpts on warship displacement)

16 May 1946

Morning Session

...

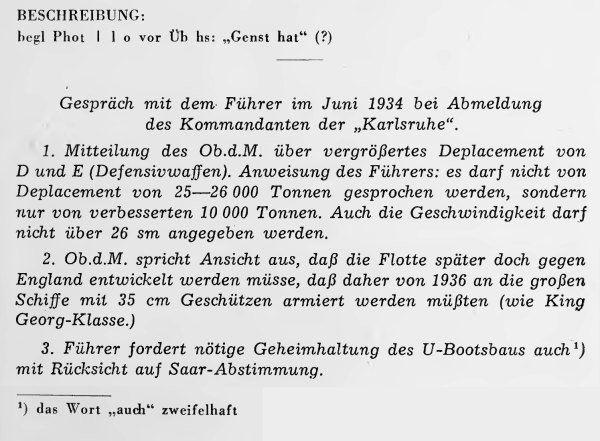

DR. WALTER SIEMERS (Counsel for Defendant Raeder): ... I now come to Document C-189, USA-44. It is in Document Book Number 10 of the British Delegation, Page 66.

I should like your comments -I beg your pardon. I should remind you that this concerns the conversation between Grossadmiral Raeder and the Führer aboard the Karlsruhe in June 1934.

Grossadmiral, will you please state your views on the three points mentioned in this brief document and which you discussed with Hitler in June 1934.

First question: Why was Hitler unwilling to reveal the increase in displacement of D and E -that is, the Scharnhorst and the Gneisenau- when, according to this document, these were defensive weapons and every expert would notice the increased tonnage of these ships and, as far as I know, did notice it?

RAEDER: At that time we were considering what we could do with the two armored ships D and E, after the signing of the impending naval pact with England -that is, the two ships which Hitler had granted me for the Navy in the 1934 budget. We had definitely decided not to continue building these armored ships as such, since we could make better use of the material at our disposal.

DR. SIEMERS: But surely you realized that every expert in the British or American or any other Admiralty would see on a voyage, as soon as he had sighted the ship, that the 10,000 tons had now become 26,000?

RAEDER: Yes, of course.

DR. SIEMERS: So that there was merely the intention...

THE PRESIDENT: Dr. Siemers, when you are examining a witness directly, you are not to ask leading questions which put into his mouth the very answer that you desire. You are stating all sorts of things to this witness and then asking him "isn't that so?"

DR. SIEMERS: I beg your pardon. I shall make every effort to put my questions differently.

RAEDER: My answer is different anyway.

DR. SIEMERS: Yes?

RAEDER: We are dealing here, in the first place, with plans. I asked permission to revise the plans for these two armored ships; first, by strengthening their defensive weapons -that is, the armor-plating and underwater compartments- and then by increasing their offensive armaments -namely, by adding a third 28-centimeter instead of 26-centimeter tower. The Führer was not yet willing to sanction a new 28-centimeter tower because, as I said before, he did not in any circumstances want to prejudice the negotiations going on with Great Britain. To begin with, therefore, he sanctioned only a medium displacement of 18,000 to 19,000 tons; and we knew that when matters reached the stage where a third 28-centimeter tower could be mounted, the displacement would be about 25,000 to 26,000 tons.

We saw no cause to announce it at this stage, however, because it is customary in the Navy that new construction plans and especially new types of ships should be announced at the latest possible moment. That was the principal reason; and apart from that, Hitler did not want to draw the attention of other countries to these constructions by giving the figures mentioned or stating the very high speed. There was no other reason for not announcing these things.

DR. SIEMERS: I should like your comments on Number 2 of the document. That has been specially held against you by the Prosecution, because there you state the view that the fleet must be developed to oppose England later on.

RAEDER: At first -as I intended to explain later- we had taken the new French ships as our model. The French Navy was developing at that time the Dunkerque class with eight 33-centimeter guns and a high speed, and we took that for our model, especially since, in Hitler's opinion -as you will hear later- there was no question of arming against England. We intended to reconstruct these two armored ships on this pattern as battleships with nine 28-centimeter guns and capable of a high speed. But then we heard that the King George class was being designed in England with 35.6-centimeter guns and, therefore, stronger than the French type; and so I said that we would in any case have to depart from the French type eventually and follow the English model which is now being built with 35-centimeter guns.

There is an error in the translation -namely, "oppose England." It says in my text that developments should follow the lines of British developments -in other words, that we should design vessels similar in type to the English ships. But they were out of date, too, shortly afterwards, because France was then building ships of the Richelieu class with 38-centimeter guns. Therefore, we decided that we too would build ships with 38-centimeter guns. That was how the Bismarck came to be built. The word "oppose" would have been quite senseless at a time when we intended to come to an agreement with Britain on terms under which we could in no way vie with her.

...

DR. SIEMERS: Grossadmiral, when did you report to Hitler for the first time on the Navy; and what was Hitler's general attitude on this occasion -toward the Navy in particular?

RAEDER: The first naval report I gave was a few days later [in February 1933] in the presence of General Von Blomberg, who in his capacity of Reich Defense Minister was my superior. I cannot give the exact date, but it was shortly afterwards.

On this occasion, Hitler gave me a further account of the principles on which I was to command the Navy. I reported to Hitler first of all on the state of the Navy; on the rather slight degree to which the provisions of the Versailles Treaty had been carried out by the Navy, its inferior strength, the Shipping Replacement Plan, and incidents concerned with naval policy, such as the Treaty of Washington, the Treaty of London, 1930, the position of the Disarmament Conference. He had already been fully informed on all these matters.

He said he wanted to make clear to me the principles on which his policy was based and that this policy was to serve as the basis of long-term naval policy. I still remember these words quite clearly, as well as those which followed.

He did not under any circumstances wish to have complications with England, Japan, or Italy -above all not with England. And he wanted to prove this by fixing an agreement with England as to the strength to be allotted to the German Fleet in comparison with that of the English Navy. By so doing, he wanted to show that he was prepared to acknowledge, once and for all, England's right to maintain a navy commensurate with the vastness of her interests all over the world. The German Navy required expansion only to the extent demanded by a continental European policy. I took this as the second main principle on which to base my leadership of the Navy. The actual ratio of strength between the two navies was not discussed at the time; it was discussed later on.

This decision of Hitler's afforded extreme satisfaction both to myself and to the whole of the Navy, for it meant that we no longer had to compete senselessly with the first sea power; and I saw the possibility of gradually building up our Navy on a solid foundation. I believe that this decision was hailed by the whole Navy with joy and that they understood its significance. The Russian Pact was later greeted with the same appreciation, since the combination of the Russian Pact and the naval agreement would have been a guarantee of wonderful development. There were people -but not in the Navy- who believed that this amounted to yielding ground, but this limitation was accepted by the majority of Germans with considerable understanding.

...

DR. SIEMERS: ... I come now to the German-British Naval Agreement and would like to ask you briefly how this Naval Agreement of 1935 came about. I am referring to Document Number Raeder-11, Document Book 1, Page 59, which contains the Naval Agreement in the form of a communication from the German Foreign Minister to the British Government. The actual content was fixed by the British, as the first few words show:

-

"Your Excellency, I have the honour to acknowledge the receipt of your Excellency's note of to-day's date, in which you were so good as to communicate to me on behalf of His Majesty's Government in the United Kingdom the following":

-

"1. During the last few days the representatives of the German Government and His Majesty's Government in the United Kingdom have been engaged in conversations, the primary purpose of which has been to prepare the way for the holding of a general conference on the subject of the limitation of naval armaments.

It now gives me great pleasure to notify your Excellency of the formal acceptance by His Majesty's Government in the United Kingdom of the proposal of the German Government discussed at those conversations, that the future strength of the German Navy in relation to the aggregate naval strength of the Members of the British Commonwealth of Nations should be in the proportion of 35:100.

His Majesty's Government in the United Kingdom regard this proposal as a contribution of the greatest importance to the cause of future naval limitation.

They further believe that the agreement which they have now reached with the German Government and which they regard as a permanent and definite agreement as from to-day between the two Governments..."

DR. SIEMERS: Very well. I should nevertheless like to point out that, according to Point 2f of this document, the British Government recognized that, as far as submarines were concerned, Germany should be allowed the same number as Britain. At that time that amounted to about 52,000 tons, or rather more than 100 U-boats. The Government of the German Reich, however, voluntarily undertook to restrict itself to 45 percent of the total submarine tonnage of the British Empire.

[Turning to the defendant.] Did you and the Navy regard such considerable restrictions as the basis for Germany's peaceful development, and was it received favorably by the Navy in general?

RAEDER: Yes, as I have already said, it was received with greatest satisfaction.

DR. SIEMERS: Since a judgment formed some years ago carries more weight than a declaration made now in the course of the Trial, I wish to submit Document Number Raeder-12, Document Book 1, Page 64. This document deals with a communication made by Grossadmiral Raeder for the information of the Officers' Corps. It is dated 15 July 1935, a month after the signing of the naval agreement. Raeder says -and I quote the second paragraph:

-

"The agreement resulted from the Führer's decision to fix the ratio of the fleets of Germany and the British Empire at 35:100.

This decision, which was based on considerations of European politics, formed the starting point of the London conferences.

In spite of initial opposition from England, we held inflexibly to our decision; and our demands were granted in their entirety.

The Führer's decision was based on the desire to exclude the possibility of antagonism between Germany and England in the future and so to exclude forever the possibility of naval rivalry between the two countries."

-

"By this agreement, the building-up of the German Navy to the extent fixed by the Führer was formally approved by England."

Then I should like to call attention to the final sentence, which is indicative of Raeder's attitude at the time:

-

"This agreement represents a signal success in the political sphere since it is the first step towards a practical understanding and signifies the first relaxation of the inflexible front so far maintained against Germany by our former opponents and implacably demonstrated again at Stresa."

RAEDER: Yes.

DR. SIEMERS: In this connection I should like to submit Document Raeder-13. This is a document which enables me -in order to save time- to dispense with the testimony here in Court of Vice Admiral Lohmann. This document will be found in Document Book 1, Page 68, and is entitled, "The New Plan for the Development of the German Navy," and is a standard work. It is a speech made by Vice Admiral Lohmann in the summer of 1935 at the Hanseatic University in Hamburg. I ask the High Tribunal to take judicial notice of the essential points of this document; and as this is an authoritative work done at the request of the High Command, I may perhaps just quote the following. Admiral Lohmann sets forth first of all that since we now had the liberty to recruit and arm troops, the Navy was then free of restrictions, but that that was not Hitler's view. I now quote:

-

"The Führer, however, chose another way.

He preferred to negotiate on German naval armament direct with Britain which, as our former adversary" -I beg your pardon; I am quoting from Page 70- "has tried for years to show understanding for our difficult position."

-

"All the more surprising, then, was the ratification of the treaty which expressed the full agreement of both governments and did not, like some armament treaties of former time, leave more embitterment than understanding in its wake.

The sense of fairness which British statesmen have retained, despite the frequently dirty ways of higher politics, came through when confronted with the unreserved sincerity of the German declarations, the dignified firmness of the German representatives, and the passionate desire for peace inspiring the speeches and acts of our Führer.

Unlike former times, the speeches of the British leaders expressed respect and recognition.

We have acknowledged this as a sign of honest willingness to understand.

The voices from the circles of British war veterans are hardly less valuable than the attitude of the official leaders.

In November 1918, for instance, when the German Fleet was taken by British squadrons to be interned in Scapa Flow, the British Commander in Chief, Lord Beatty, the great foe of our Admiral Hipper, sent the famous signal, 'Do not forget that the enemy is a contemptible beast.'

This Grand Admiral expressed his dislike for Germany on many occasions, but on 26 June this same Lord Beatty stated in the House of Lords, 'I am of the opinion that we should be grateful to the Germans.

They came to us with hands outstretched, announcing that they agreed to the ratio of 35:100.'

If they had submitted other proposals, we could not have prevented them.

We may be truly grateful for the fact that there is at least one country in the world whose competition in regard to armament we do not need to fear."

Then as evidence of the basis for comparison with German U-boats, I should like to point to Page 76 where the figure mentioned is 52,700 tons. It is a historical fact -which is set down here- that France took no part in this limitation and at that time was the strongest U-boat power with her 96,000 tons, 96 ready and 15 under construction. It is also a historical fact that Germany -and this is shown on the same page- had agreed to abolish submarines, having had to destroy 315 after the first World War.

Grossadmiral, did this accord with the British Fleet apparent in these documents show itself on another, or on any particular occasion?

RAEDER: I tried to maintain this good understanding and to express these sentiments to the British Navy as, for instance, when I was informed of the death of Admiral Jellicoe through a phone call from an English news agency. He stood against us as the head of the English Fleet in the first World War, and we always considered him a very chivalrous opponent. Through this agency I gave a message to the English Fleet.

THE PRESIDENT: I doubt if this really has any effect on the issues we have to consider.

RAEDER: In any event, I tried to bring about a good understanding with the British Navy for the future and to maintain this good understanding.

DR. SIEMERS: On 17 July 1937 a further German-English Naval Agreement was signed. I am submitting this document as Document Raeder-14, Document Book 1, Page 81. This is a rather lengthy document only part of which has been translated and printed in the document book; and in order to understand the violation with which the Prosecution charge us, I must refer to several of the points contained in this document.

The agreement concerns the limitation of naval armaments and particularly the exchange of information on naval construction. In Article 4 we find the limitation of battleships to 35,000 tons, which has already been mentioned; and in Articles 11 and 12 -which I will not read because of their technical nature but would ask the Tribunal to take note of- both governments are bound to report annually the naval construction program. This must be done during the first 4 months of each calendar year, and details about certain ships -big ships in particular- 4 months before they are laid down. For a better understanding of the whole matter, which has been made the basis of a charge against the defendants in connection with the naval agreement, I may refer to Articles 24 to 26. The three articles show...

THE PRESIDENT: Can you summarize these articles?

DR. SIEMERS: Yes. I did not intend to read them, Your Honor. I just want to quote a point or two from them.

These articles enumerate the conditions under which either partner to the agreement could deviate from it. From the start, therefore, it was considered permissible under certain conditions to deviate from the agreement, if, for instance, (Article 24) one of the partners became involved in war, or (Article 25) if another power, such as the United States or France or Japan, were to build or purchase a vessel larger than those provided for in the agreement. In this article express reference is made to Article 4 -that is, to battleships of 35,000 tons- in the case of deviation, the only obligation was to notify one's partner. Article 26 states a very general basis for deviation from the agreement-namely, in cases where the security of the nation demands it such deviation is held to be justified. No further details are necessary at this point.

SIR DAVID MAXWELL-FYFE (Deputy Chief Prosecutor for the United Kingdom): My Lord, the deviation is subject to notification of the other party under Subarticle 2. It was just relevant in Article 26 -any deviation is subject to notification to the other party of the deviation to be embarked on.

THE PRESIDENT: Is it, Dr. Siemers?

DR. SIEMERS: Yes, of course. I believe...

THE PRESIDENT: Do the Prosecution say that this agreement was broken?

DR. SIEMERS: Yes. With reference to the remarks just made by Sir David, I would like to say that I pointed out that such deviation was permitted under these conditions, but that there was an obligation to notify the other partners. Perhaps that did not come through before.

[Turning to the defendant.] Was this agreement concluded, Admiral, in 1937, from the same point of view which you have already stated? Are there any other noteworthy facts which led to the agreement?

RAEDER: In 1936, as well as I remember, the treaties so far made by England with other powers expired, and England was therefore eager to renew these treaties in the course of 1936. The fact that we were invited in 1937 to join in a new agreement by all powers meant that Germany would henceforth be completely included in these treaties.

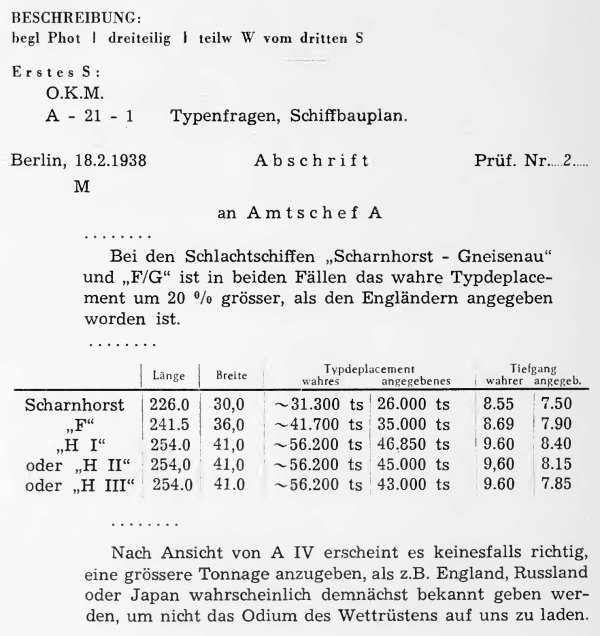

DR. SIEMERS: The Prosecution have accused you of violating this German-English Naval Agreement, and this charge is based on Document C-23, Exhibit USA-49, in the British Delegation's Document Book 10, Page 3. This document is dated 18 February 1938. It has been mentioned repeatedly in these proceedings and begins as follows, "The actual displacement of the battleships Scharnhorst, Gneisenau and F/G is in both cases 20 percent greater than the displacement stated to the British." Then we find a list which shows that the displacement of the Scharnhorst was given as 26,000 tons but was actually 31,300 tons, and that the draught stated one meter less than was actually the case. And the "F" class, that is, the Bismarck and Tirpitz, were listed as 35,000 tons but had an actual displacement of 41,700 and a difference of 80 centimeters in draught. Therefore, according to what we have seen, there is an evident infringement of the treaty. Grossadmiral, I am assuming that you do not dispute this violation of the treaty?

RAEDER: No, in no way.

DR. SIEMERS: Certainly, at the time of this document there were only four battleships in question: Scharnhorst, Gneisenau, Bismarck, and Tirpitz...

THE PRESIDENT: It seems you are again stating these things to the Tribunal, making statements instead of asking questions of the witness.

DR. SIEMERS: I believe, Mr. President, that I was incorporating my documentary evidence in order to show the connection, so as to make clear what we are dealing with. I was about to put the question: Were the four battleships mentioned actually in commission when this document was drawn up?

RAEDER: No, they had not yet been commissioned.

DR. SIEMERS: None of these four battleships?

RAEDER: No.

DR. SIEMERS: If I am permitted to do so, I may say that the exact dates on which these ships were commissioned -dates which the defendant can hardly repeat from memory- can be seen from Point IV of Lohmann's affidavit, Document Number Raeder-2.

THE PRESIDENT: I think you must prove them. You cannot state them without proving them.

DR. SIEMERS: Yes, certainly, Your Honor.

I am referring to Document Number Raeder-2, which has been submitted to the Tribunal already. This is the affidavit by Lohmann, on Page 5. I quote from Document Book 1, Page 8:

-

"Within the limits defined by the German-English Naval Agreement, the German Navy commissioned four battleships.

I append the dates of laying down the keel, launching, and commissioning, as far as I can still determine them. Scharnhorst: laid down keel, exact date cannot be determined; launched, 3 October 1936; commissioned, 7 January 1939. Gneisenau: laid down keel, date cannot be determined; launched, 8 December 1936; commissioned, 31 May 1938. Bismarck: laid down keel, 1936; launched, 14 February 1939; commissioned, 2 August 1940. Tirpitz: laid down keel, 1936; launched, 1 April 1939; commissioned, 1941."

Document Number Raeder-15 is an affidavit -I beg your pardon- it is in Document Book 1, Page 94. This document deals with an affidavit deposed before a notary at Hamburg by Dr. Ing. h.c. Wilhelm Süchting and is important for the refutation of Document C-23, and for that purpose I should like to quote:

-

"I am the former Director of the shipbuilding yard of Blohm & Voss in Hamburg.

I was with this firm from 1937 to 1945 "-pardon me-" from 1907 to 1945 and I am conversant with all questions concerning the construction of warships and merchant ships.

In particular, as an engineer I had detailed information about the building of battleships for the German Navy.

Dr. Walter Siemers, attorney at law of Hamburg, presented to me the Document C-23, dated 18 February 1938, and asked me to comment on it.

This document shows that the Navy, contrary to the previous agreement, informed the British that the battleships Scharnhorst and Gneisenau -as well as other intended constructions- had a displacement and draught of about 20 percent less than was actually the case.

"I can give some details to explain why this information was given. I assume that the information given to the British -information which according to naval agreement 4 had to be supplied 4 months before the keel was laid down- was based on the fact that the battleships Scharnhorst and Gneisenau were originally intended to have a displacement of 26,000 tons and a draught of 7.50 meters and the battleship "F" (Bismarck) a displacement of 35,000 tons and a draught of 7.90 meters, as stated.

"If these battleships were afterwards built with a greater displacement and a greater draught, the changes were the result of orders given or requests made by the Navy while the plans were being drafted and which the construction office had to carry out. The changes were based upon the viewpoint repeatedly expressed by the Navy -namely, to build the battleships in such a way that they would be as nearly unsinkable as possible. The increase of the tonnage was not meant to increase the offensive power of the ship" -I beg your pardon, Mr. President. I shall be finished in a moment- "The increase of the tonnage was not meant to increase the offensive power of the ship but was done for defensive and protective purposes."

-

"As time went on, the Navy attached more and more importance to dividing the hull of the battleship into a greater number of compartments in order to make the ship as unsinkable as possible and to afford the maximum protection in case of leakage.

The new battleships were therefore built broad in the beam with many bulkheads, only about ten meters apart, and many longitudinal and latitudinal bulkheads outside the torpedo bulkhead.

At the same time, both the vertical and the horizontal armor-plating were, as far as my information goes, heavier and composed of larger plates than those used by other navies. In order..."

THE PRESIDENT: In other words, his explanation is that they were altered in the course of construction for technical reasons. It does not matter what the technical reasons are.

DR. SIEMERS: I beg your pardon, Mr. President, but I do believe that when we are dealing with a clearly-established violation of a treaty, the manner of this violation is of some importance. I do not believe that each and every violation of a treaty can be described as a war crime. The point is whether this violation of the treaty was a war crime in the sense of the Charter -in other words, whether it was motivated by the intention of waging a war of aggression. An insignificant violation of a kind which, after all, is found in every commercial lawsuit cannot be a crime.

THE PRESIDENT: The affidavit is before us. We shall read it. In fact, you have already read the material parts of it.

...

[The Tribunal recessed until 1400 hours.]

Afternoon Session

...

[The Defendant Raeder resumed the stand.]

DR. SIEMERS: Herr Grossadmiral, you just saw the affidavit of Dr. Süchting. I ask you: Is it true, or rather -not to confuse you I will ask- on what did the Navy base its ideas about enlarging the battleships by about 20 percent?

RAEDER: Originally there was no intention to enlarge the ships by 20 percent. But at the time when we resumed battleship construction, when we could see that we would have a very small number of battleships in any case, it occurred to us that the resistance to sinking of ships should be increased as much as possible to render the few we had as impregnable as possible. It had nothing to do with stronger armament or anything like that, but merely with increasing the resistance to sinking and to enemy guns. For this reason a new system was worked out at that time in order to increase and strengthen the subdivision of the space within the ship. This meant that a great deal of new iron had to be built into the ships. Thereby the draught and the displacement were enlarged. This was unfortunate from my point of view, for we had designed the ships with a comparatively shallow draught. The mouths of our rivers, the Elbe, Weser, Jade, are so shallow that ships with a deep draught cannot navigate all stages of the rivers. Therefore, we had these ships built broad, intending to give them a shallow draught; but by building in these many new latitudinal and longitudinal bulkheads, we increased the draught and also the displacement.

DR. SIEMERS: Were these disadvantageous changes, which took place during construction, due in part to a comparatively limited experience in battleship construction?

RAEDER: Yes. Since the designers in the High Command of the Navy and the designers and engineers in the big shipyards had not built any heavy warships for a very long time, they lacked experience. As a result, the High Command of the Navy had to issue supplementary orders to the shipyards. This in itself was a drawback which I tried hard to overcome.

DR. SIEMERS: Did the construction of these four battleships surpass the total tonnage accorded by the naval agreement?

RAEDER: No, the total tonnage was not overstepped until the beginning of the war.

DR. SIEMERS: Your Honors, in this connection I should like to refer to Document Raeder-8, which has already been submitted in Raeder Document Book 1, Page 40, under II. In this affidavit Lohmann gives comparative figures which show how much battleship tonnage Germany was allowed under the naval agreement. Please take notice of it without my reading all the figures. What is important is that, according to comparison with the British figures, Germany was allowed to have 183,750 tons. At that time she had three completed armored cruisers [Panzerschiffe] with 30,000 tons -which is shown here- so that according to this affidavit 153,750 tons still remained.

With reference to Document Raeder-127, I should like to submit a short correction, because Grossadmiral Raeder, in looking through the affidavit, observed that Vice Admiral Lohmann made a mistake in one figure. The mistake is unimportant in terms of the whole, but in order to be absolutely fair and correct I thought it necessary to point it out to Vice Admiral Lohmann. Instead of 30,000 it should actually read about 34,000 tons, so that there is a difference, not of 153,750 tons but of 149,750. According to the naval agreement, we were allowed to build 146,000, the final figure, so that the result is not changed. Admiral Lohmann's mistake -as the Tribunal know- can be attributed to the fact that we were very limited in our material resources.

RAEDER: May I add a remark to what I said before? The statement of these displacements deviated from the terms of the treaty insofar as only the original construction displacement or draught was reported and not the draught and displacement which gradually resulted through these changes in the course of the planning of the construction.

DR. SIEMERS: In addition, may I refer the honorable Court to the following: The Naval Agreement of 1937 was changed by the London Protocol of 30 June 1938. I refer to Exhibit Raeder-16. My secretary just tells me it is not here at the moment; I will bring it up later. It is the last document in Raeder Document Book 1, Page 97.

May I remind the Court that Document C-23 is of February 1938. By this London Protocol, at the suggestion of the British Government, the limitation on battleship tonnage to 35,000 tons was changed because the British Government, as well as the German Government, realized that 35,000 tons was too low. As the protocol shows, effective 30 June 1938, the battleship tonnage was raised to 45,000 tons. Thereby this difference in the battleships, referred to in Document C-23, was settled a few months later.

...

20 May 1946

Morning Session

...

SIR DAVID MAXWELL-FYFE: Well, now I just want you to look for a moment at the document which is on Page 3 of Document Book 10, which you did refer to in your examination-in-chief. That is Document C-23, about the displacement of the Scharnhorst and the Gneisenau and the Tirpitz and the Bismarck and the other ships.

Now, you are familiar with that document; we have discussed it.

RAEDER: Yes. I know the documents.

SIR DAVID MAXWELL-FYFE: Well now, that is dated the 18th of February, 1938. Germany didn't denounce the Anglo-German Naval Treaty until after the British guarantee to Poland in April 1939, which is 14 months later.[1] Why didn't you simply send a notification to Great Britain that the displacements had come out 20 percent bigger because of defensive matters in construction? Why didn't you do it?

[Note by editor: 1. Hitler announced his decision to abrogate the Anglo-German Naval Treaty speaking before the Reichstag on 28 April 1939].

RAEDER: I cannot tell you that today. We explained recently how the displacements gradually increased through quite insignificant changes to our own detriment.

SIR DAVID MAXWELL-FYFE: Yes. Really, Defendant, I have got that well in mind. We have got the reason why the displacements came out bigger, and I don't think you are prejudicing yourself if you don't repeat it, but just look at the bottom of that page, because I think you will find the reason which you can't remember there; won't you?

-

"Nach Ansicht von [Marineausbildungsabteilung] A IV erscheint es keinesfalls richtig, eine grössere Tonnage anzugeben, als z.B. England, Russland oder Japan wahrscheinlich demnächst bekannt geben werden, um nicht das Odium des Wettrüstens auf uns zu laden."

"In the opinion of [Naval Development Office] A IV, it would be quite wrong to report a larger tonnage than that which will probably be published shortly, for instance, by England, Russia, or Japan, so as not to bring upon ourselves the odium of an armament race."

RAEDER: Yes, that was intended for a future date. We wished in no circumstance to create the impression that we were increasing the offensive power of our ships.

....

SIR DAVID MAXWELL-FYFE: ... Just turn over, if you will be so good, to Page 66 of Document Book 10, Page 285 of the German document book, Document Number C-189, My Lord.

[Turning to the defendant.] Now, I want to raise just this one point on which you made a point in your examination and which I must challenge. You say in Paragraph 2:

-

"The Commander-in-Chief of the Navy expresses the opinion that later on" -and I ask you to note the words "later on"- "the fleet must anyhow be developed against England and that therefore from 1936 onwards the large ships must be armed with 35 centimeter guns."

RAEDER: I explained the other day that we are dealing here with the question of keeping up with other navies. Up to that time we were keeping up with the French Navy which had 33 cm guns. Then England went beyond that in mounting 35.6 cm guns on her ships and then, as I said before, France went beyond England in using 38 cm guns. Thus I said to the Führer that our 28 cm guns which we believed we could use against the French Dunkerque class would not be heavy enough, and that we would have to take the next bigger caliber, that is 35.6 like those of the English ships. That was never done because the French began to use 38 cm guns and our Bismarck class followed the French lines.

That comparison of calibers and classes of vessels was at that time quite customary and was also ...

SIR. DAVID MAXWELL-FYFE: You told us all that before and my question is a perfectly simple one; that this document in the original German, when you say "gegen England" is exactly the same as in your song Wir fahren gegen England. It means against, in antagonism and directed against, and not in comparison. That is what I am putting to you and it is a perfectly short point.

Are you telling this Tribunal that "gegen England" means in comparison with England?

RAEDER: That is what I want to say; because it says "develop gegen England" and at that time we had not even signed the Naval Agreement. It is hardly likely that I would consider following an anti-British policy.

...